When I walked into the cabinet room in the Centre Block of Parliament for my first cabinet meeting in 2015, I remember feeling a mixed sense of excitement and trepidation. This moment was the culmination of several years of hard work for me as the Member of Parliament for Durham, but it was also the result of several decades of dreaming for someone who wanted to serve the country in higher office. The moment also left me thinking about the gravity of the situation, as I hoped to contribute to the critical debates and decisions facing the country in a meaningful way.

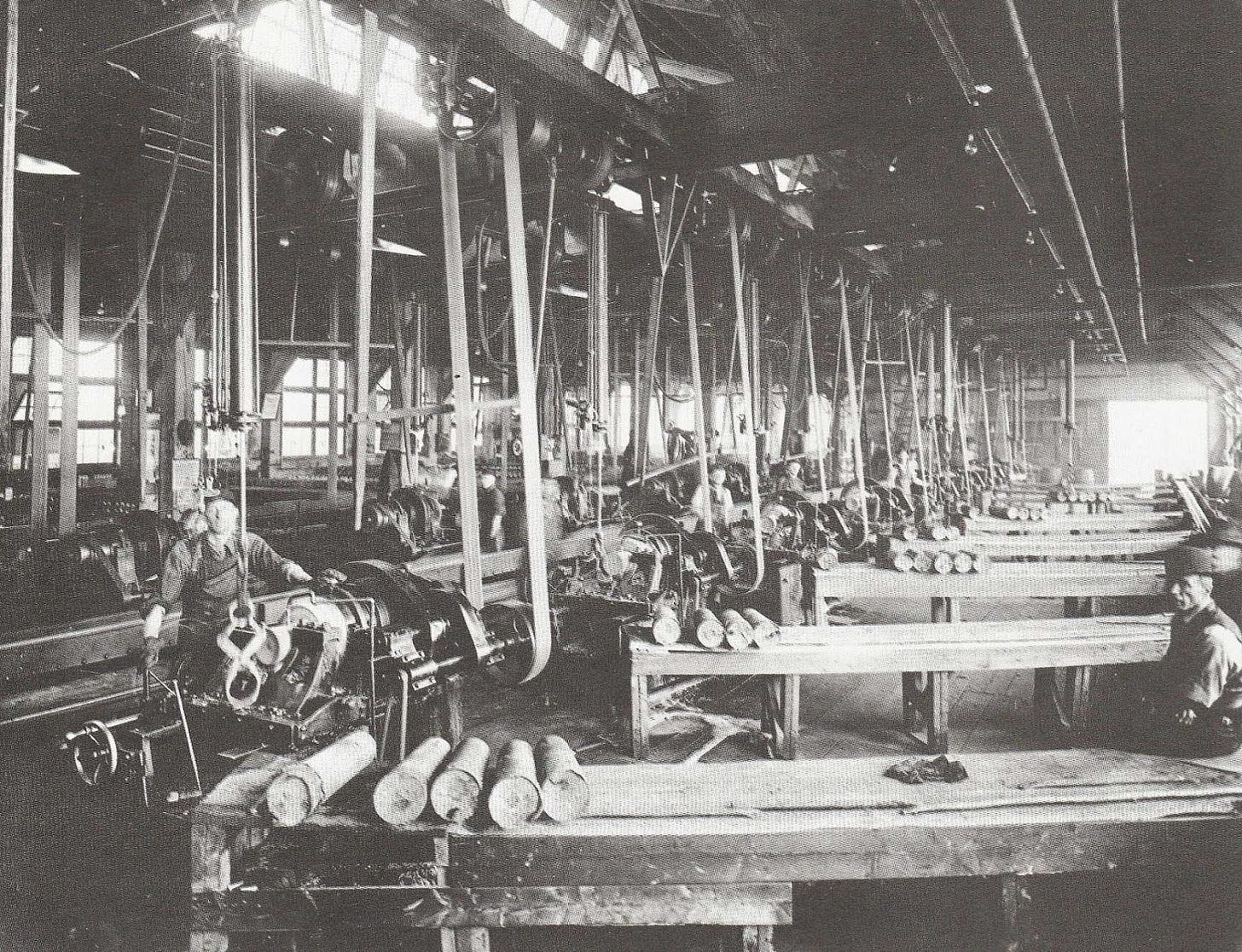

I was early for the meeting and was savouring this special moment when a painting on the wall of the cabinet room caught my eye. It was from the Canadian War Museum collection that adorned many of the official spaces in Ottawa. What drew me in was the centrepiece of the painting. It featured ships being built in an old dry dock with the shipyard workers involved in the construction featured in the foreground. I had never seen the painting before and it appeared to be something from the Great War given that a horse was being used to haul materials. As I leaned in to read the nameplate beside the painting, I was blown away by where this shipyard was located.

Shipbuilding in Ashbridges Bay, Toronto, 1918

Canada built ships in the Beaches? This was the question I asked myself as I stared at the canvas. I knew Ashbridge’s Bay very well because I had run the trails in that area for the years that Rebecca and I had lived in the Beaches neighbourhood of Toronto1. The Beaches (or ‘The Beach’ to purists) is a stretch of the Lake Ontario shoreline beginning with the iconic RC Harris water treatment plant in the east and ending with Ashbridge’s Bay in the west. It is comprised of beaches, parks, and quaint shops along Queen Street a block up from the beachfront. It is generally an area of outdoor recreation with the exception of the waste treatment and water filtration plants that bookend the neighbourhood. I knew there had been an amusement park located there a century ago, but I had never heard about any industry in the area. The thought of the Beaches being a major centre of wartime industry was almost hard to believe.

With my curiosity piqued, I later tracked down some information about what happened in Ashbridge’s Bay during the First World War. The history I found revealed what our country can really achieve when we seize the moment. It is a history we would do well to replicate today.

Drain the Swamp

Not only did ships get built in Ashbridge’s Bay during the Great War, but I learned it was also home to the largest electrical steel plant in the world . A plant that was purpose built for the war effort and was closed and dismantled only a few years after the war ended. The steel plant was built on reclaimed land in Ashbridge’s Bay that served almost as a pop-up economy to drive the Great War supply effort.

In many ways, the Great War was the first ‘Canadian moment’. Not yet 50 years old as a country, Canada wanted to seize the opportunity to step up as a former British colony and play a serious role in the war effort both on the front lines and in the critical supply mission. This first Canadian moment led to Ashbridge’s Bay being transformed from a swampy marsh along the eastern Toronto waterfront into what could be described as the most important multi-purpose industrial site in Canada during the Great War. What was even more remarkable was the fact that Ashbridge’s Bay went from fallow to factory in less than a year. Build, baby, build, indeed.

This remarkable transformation was made possible by the Imperial Munitions Board (IMB). The IMB was created in 1915 to lead the industrialization of the Canadian economy for the purposes of the war effort. It was born out of the Shell Crisis of 1915 that paralyzed the British parliament and caused a crisis of confidence for the government due to the lack of shells and munitions for a nation at war2. The British government turned to Canada to help with the dilemma through the creation of a new agency to be led by business leaders and military officers to drive the munitions supply initiative at a breakneck speed to help win the war.

Prime Minister Robert Borden accepted the British request and dispensed with the ineffective and scandal-ridden Canadian Shell Committee that had been the fiefdom of the controversial Militia Minister Sam Hughes. The Hughes board was dismissed and the new IMB board created through an Order-in-Council with a reporting authority directly to the British War Office. Toronto industrialist Joseph Flavelle was selected as the Chairman of the IMB and was given remarkable power to drive investment and production. Within weeks, Flavelle had organized the IMB into twenty different departments and had production plans underway for everything from shells and explosives to timber, steel and shipbuilding. By the end of the war, the IMB had constructed several national factories through its own subsidiaries and had contracted with over 650 different production facilities across Canada to help the allies win the war3.

The British Forgings steel plant in Ashbridge’s Bay is a case study of the success of the IMB. The steel plant went from a proposal in late 1916 to construction of the largest electrified steel plant in the world that was pouring steel by the summer of 1917. The IMB empowered the project with a $3 million grant and provision of the land for the plant courtesy of the Toronto Harbour Commission.

The IMB also oversaw construction of ships for merchant shipping, as the British merchant fleet had been disrupted by the war as shipyards focused on supporting the Royal Navy. In 1917, the IMB was asked to help address the shortage of ships for the merchant marine and it began placing orders for ships made of both steel and wood given the shortages in steel the war was causing. The newly formed Toronto Shipbuilding Company leased land in Ashbridge’s Bay to build ships and received an IMB commission for two, 3200 tonne wooden steamship vessels. It was these two vessels - the War Ontario and the War Toronto - that are featured in the painting by Robert Ford Gagen.

By the time the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 ending the war, the British Forgings steel plant had produced 48,000 tons of steel and more than 3 million shells for the allied war effort4. Nineteen ships had been built over the course of the war by Toronto-area shipbuilders, including the War Ontario and War Toronto built in Ashbridge’s Bay. These ships were two of 46 wooden vessels commissioned by the IMB alongside 26 steel vessels for the war effort. The shipbuilding industry in Toronto was so significant to the war effort that the Canadian War Memorials Fund commissioned artist Robert Ford Gagen to memorialize this wartime industrialization. He produced seven works spanning several shipyards in Toronto including the painting that was the inspiration for this essay5.

You might say that the IMB literally ‘drained the swamp’ for the first time in North American politics. They moved away from the corruption of the Hughes’ led Shell Committee and empowered the Canadian economy in a way nobody thought was possible. The country seized the moment and there is much we can learn from it.

History Rhymes

I helped kick off the Transition Accelerator’s 'Building the Future Economy Summit in Ottawa last week. I was asked to help frame the moment the country and world is facing in a section of the agenda entitled ‘The Opportunity’. The conference was focused on seizing Canada’s current window of opportunity to get big things done, but to do so with the knowledge we have developed as a country on sustainability, reconciliation and national unity.

With the tongue-in-cheek informal title of the “Get Sh*t Done” conference, the Transition Accelerator brought together leaders from industry, academia, finance, Indigenous groups and the non-profit sectors to catalyze a plan for the opportunities in front of us in a way that was both smart and swift. The most common comment from participants throughout the day was that Canada was having ‘a moment’ that we must not let pass us by. It was an engaging group and a terrific set of conversations about the country.

My speech was focused on the notion of building sovereign capability to make sure that our economic security has a strong element of self-reliance and domestic capacity in critical areas of a modern economy. I began my presentation with a slide featuring the Shipbuilding in Asbridges Bay, 1918 painting and an abridged version of this essay. I challenged attendees to draw inspiration from the past for the challenges we are facing today by showing how swiftly we can get things done if there is political will, business acumen, public support and social license.

When the Great War began in 1914, Ashbridge’s Bay was a swamp. The Royal Canadian Navy was only four years old and had only 2 ships and roughly 200 personnel. It would have appeared at the time that Canada was less capable of responding to ‘the moment’ than we are today as a G7 economy. Canada did respond and the country was transformed in a positive way. By the end of the war, Ashbridge’s Bay was a critical war production hub and we had built hundreds of ships for the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and merchant marine. There were over 5000 Canadian serving in the RCN and an incredible 10% of our modest population of 8 million had served in the war effort. Canada and Canadians responded valiantly in the Great War.

The rest of my remarks focused on the need to seize the moment and build sovereign capability into our thinking to ensure that we can safely traverse the choppy waters of de-globalization, populism and international realignment. We are not at war, but the world has become dramatically more uncertain and unforgiving. I demonstrated this with my next slide that reminded people of the time during the COVID-19 pandemic when the 3M plant in Michigan was prevented from delivering Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to Canada by order of the President of the United States. We also remember the planes that were taking off from China with PPE being sold to the highest bidder. All of this came mere months before vaccine nationalism and ventilator shortages showed the risk of relying on others in a time of crisis. Healthcare capacity is clearly a critical sovereign capability.

I also focused on defence and security and evoked the Gagen painting when talking about the fact that China had built more ships in one of its national shipyards in 2024 than all US shipyards had produced since the Second World War. In fact, this critical deficit in shipbuilding capacity is a major driver of the 232 tariffs the United States is imposing on steel and aluminum that Canada has only started taking seriously. I also raised the question of whether we wanted to have our space launch capability in the hands of others and whether we wanted to rely on the whims of Elon Musk for satellite communications. I also spoke about the importance of subsea cables and over the horizon capabilities in the Arctic in order to assert our sovereignty in the high north at a time when others are questioning it. This was part of a discussion of the need to have a robust and innovative defence industry to supply the Canadian Armed Forces and our allies in this time of global uncertainty. There are Canadian innovators and solutions for all of these questions if we start thinking about these capabilities as a part of our sovereignty and independence as a country.

I also spoke about the importance of energy security and food security as part of our economic security and how we should not abandon our desire to become more self-reliant even if relations with the United States return to some form of a new normal. For me, a critical element of this Canadian moment is for the country to realize that the world has changed and that we must become more self reliant and self confident on a permanent basis.

Later in the afternoon of the conference, the Canadian Senate passed Bill 5, the One Canadian Economy Act, just a few hundred metres from where we were having our conference discussions. While there was still some trepidation in the room about the bill being rushed and insufficiently attentive to criticism from some Indigenous leaders, there seemed to be nobody in attendance that wanted to change course of seizing the opportunity in front of Canada. There was confidence that we can and must move swiftly and that we can do so with sustainability and reconciliation as part of our national calculus.

The New Flavelle ?

Little did I know that the day before my speech, Minister Tim Hodgson had used a similar comparison to wartime Canada to encourage Canadians to embrace this moment to build things and get projects done for Canada. Hodgson served briefly in the Canadian Armed Forces before a successful career in business. He is a great patriot and has personally (and very quietly) helped dozens of Veterans in their transition out of uniform. I only know this because several of them have told me how important his help was. I have always had deep respect for him and his work with Veterans. In fact, he has consistently been one of the biggest supporters of the True Patriot Love charity for military families that I was involved in creating in 2009.

While Hodgson used allusions to the Second World War and not the First World War, the sentiment is the same. We need to channel the strength and success of Canada in the past to overcome the naysayers who think Canada cannot get things done today. We can and we must build and be prepared to stand on our own. As Sir John A Macdonald himself once said, “[w]e are a great country, and shall become one of the greatest in the universe if we preserve it; we shall sink into insignificance and adversity if we suffer it to be broken”.

I want Tim to succeed in his mission because I want Canada to succeed. We need to build things in Canada again. We need to get our energy to market. We need to innovate and win. We need to defend our true north from the seabed floor to the stars in the sky. We need to be sovereign in all that we do, but always willing to stand with others who embrace our values and respect our liberty. And we need to do all of these things with the confidence of the great country that we are.

Godspeed to the modern day Flavelle!

Let’s Get Sh*t Done!

Happy Canada Day!

Personal Note: we just returned to this lovely neighbourhood last year

Toronto’s Waterfront at War 1914-1918, Michael B. Moir - https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/download/11574/12520/

https://wartimecanada.ca/sites/default/files/documents/Canada'sPart.1921_1.pdf

In a twist of irony, the Shell Crisis was led by a Canadian-born Conservative policitian as Leader of the Opposition during the war. Bonar Law and the Conservatives pushed the issue leading to a coalition government. Law was born in New Brunswick before Confederation and became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Checklist of the War Collections, R.F. Wodehouse at page 28: https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/checklistofwarco00wode/checklistofwarco00wode.pdf

We will get a lot more s*** done if we amend the Impact Assessment Act.

Erin, thanks for this. On point for sure! I have also used our participation in both world wars as examples of what we can do when necessary. It can be done again, but it requires true leadership, focused objectves, strategic clarity, perseverance, and of course capital. Keep up your good work!