Das Beste kommt noch! (The Best is yet to come!)

How our society can learn from the good character of our veterans

Four days with little sleep, a lot of rain, hurricane force winds, rocky mountain climbs and I didn’t want it to end. As Remembrance Week begins this year, I am thinking a lot about the True Patriot Love Expedition I was a part of a month ago. This expedition retraced the steps of the famed First Special Service Force (known as the Devil’s Brigade) along their mountainous training routes on the Continental Divide Trail a short drive from Helena, Montana. The expedition was assembled was to draw attention to our military history while raising funds and awareness for those who serve today, but as I look back on the mission I realize that it was about much more than that. The grueling trek through the mountains of Montana was less about our group recreating a march from the past, but more about coming together to find a path towards purpose for the future.

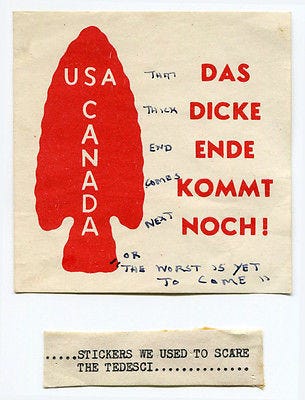

The Worst is Yet to Come was the psychological operations calling card of the Devil’s Brigade during the Second World War. The soldiers would drop these cards in and around German positions in Italy to strike fear in their enemy by warning them that some of the best soldiers from Canada and the United States were coming for them. The First Special Service Force (FSSF) was truly a cross-section of the very best our two nations had to offer. A unit comprised of approximately 60% American troops and 40% Canadian, the soldiers were put through their paces with rigorous training at Fort William Henry Harrison in Helena, Montana. They were trained in airborne deployment, mountain operations, hand to hand combat and other commando-style tactics that made the FSSF the first dedicated unit of Special Operators. The fact that two close allies forged this unit together also explains why both the Canadian special forces community (Joint Task Force 2 (JTF-2) and the Canadian Special Operations Regiment (CSOR)) and the U.S. special forces community (the Green Berets and Delta Force) both view the FSSF as their founding unit.

The Devil’s Brigade was deployed to the Aleutian Islands in the Pacific theatre in the summer of 1943 before being redirected to the ferocious fighting in Italy months later. In fact, the FSSF arrived in Italy eighty years ago this month. It was in Italy where the Devil’s Brigade legend was forged. One of the most famous soldiers from the unit, Tommy Prince, was a Manitoba-born soldier whose exploits led him to become one of the most decorated soldiers of the FSSF and Canada’s most decorated Indigenous soldier of the war. His scouting was the stuff of legend because he would don traditional moccasins to stealthily penetrate far behind enemy lines to report on enemy capabilities, disrupt their operations and no doubt leave the Devil’s Brigade calling card on his way out.

Our expedition team was proud to pay tribute to Tommy Prince at the Montana Military Museum that honours him and his FSSF comrades. It also happened to be the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, so we could honour his tremendous service for Canada and remember the poor treatment he received after the war. It is both inspiring and heartbreaking to know that Indigenous soldiers gave it all for their country only to be relegated once again to second class status when they returned from war.

The United States Congress presented the Devil’s Brigade with a Congressional Gold Medal in 2015 to honour the incredible service and sacrifice of this unit during the Second World War. I had the honour of representing Canada at the ceremony and in my remarks I spoke about Tommy Prince and the special nature of these men who were prepared to lay down their lives for their friends.

The Best is Yet to Come

Spending time with some Canadian and American veterans and some active soldiers on the Devil’s Brigade Expedition renewed my faith in our two countries and reminded me that during Remembrance Week we can both honour and learn from those who serve our country.

Most of the veterans on the expedition were from special forces units and many were on a personal journey of transition out of uniform into civilian life. They not only had to find a new calling after decades of work as a soldier, but they were each carrying a load that was invisible to most people. Each of them had the burden of trauma from injuries and experiences they encountered as a result of their service for our two countries. How they soldier on with this burden, or perhaps in spite of it, reveals a lot about what makes them exceptional citizens.

“Hard men do hard things and that bonds them”

- a Canadian veteran

Service. Sacrifice. Loyalty. Honour. To the Canadian and American veterans on the Devil’s Brigade Expedition, these values represent both the reason they serve and the conduct of their service. The identity of a soldier is constructed upon making your own self-interest secondary to the needs of your comrades and your country. At a time when our society appears to be realigning itself based on identity and ego, the altruism and character demonstrated by our soldiers is refreshing. In fact, it gives me hope that these values can guide our society out of some of the challenges we are now facing.

“Hard men do hard things and that bonds them” said one veteran on our trek. “I wish I was in that vehicle when they were hit by the IED…” said another, as he reflected on the deep pain of survivor’s guilt. This group of men had already demonstrated remarkable bravery and dedication during their time in uniform, yet they were plagued by regrets of not having sacrificed even more. I quietly wept as these warriors shared their feelings around the campfire near the end of our journey. We were all chilled, tired and sore from the expedition, but these feelings faded away as we listened to stories of loyalty, duty, courage and pain. I felt privileged to be trekking with these great citizens. Anglophone, Francophone, Officers, NCOs, Canadian, American - each had different backgrounds and experiences - but all of their reflections had the same themes. Their love for their fellow soldiers. Their intense pain for the loss of their friends. And their enduring love for their country and their regiment.

We live in an age where people express anger and outage on social media, but are increasingly not prepared to get off the couch to serve a higher purpose. Volunteerism is going down, while protest and activism is going up. Higher education is become siloed and unwilling to foster respectful debate at the same time that younger Canadians are working less and participating in fewer sports and activities to give them real life experience. We are producing a generation of young Canadians (and Americans) who have had far less interaction and socialization with their fellow citizens and less opportunities to learn how to work with others. Our populations have grown, but so has our isolation. The US Surgeon General has declared that there is an epidemic of loneliness, and I fear that it could have a far greater impact than the pandemic we just went through.

The epidemic of loneliness touches all parts of our society, but perhaps it is most acute with young people and particularly young men. Mental health conditions and suicide rates are on the rise across the country. There is also a sense that young men are struggling as a demographic group. I observed this phenomenon during my time in public life and it seemed to get worse in the last five years. In my experience, the ‘angry young man’ seemed to often be someone who was impatient for recognition, or resentful of their position despite not having experienced a lot of personal hardship. I believe that this dislocation stems from the loss of real interaction and exposure to the challenges that would have normally come with play, sports and socialization through groups like Boy Scouts or even Sunday school. This may sound old fashioned, but these traditional sources of personal experience helped many young men - myself included - find their identity and purpose through these engagements. Without these experiences, young men are left to forge their identity through social media. The trouble with that is that followers do not replace friends. Influencers do not replace parents, coaches or mentors. And at a base level, watching does not replace doing. On social media, everything seems happy and easy, but that is not how life is.

Some commentators have attributed this ‘lost young men’ phenomenon to decades of equality policies causing resentment, or to the changing nature of work and the role of men in society, but I believe it is much more basic than that. Too many young people are finding it hard to determine their purpose in life because they are being exposed to fewer experiences and fewer guides along the way. In the last decade, young men are being guided by algorithms in their search for meaning and that is drawing them into personalities and patterns that are only compounding their sense of isolation. Too many young men are no longer looking up to their father, a teacher or their hockey coach as guides to becoming a man, but are being directed to wealthy crypto bros, cocksure opinion leaders and reality show hucksters to show them the way.

My time in the mountains of Montana convinced me that we need new ways to promote purpose in our young people and elevate the value of service towards your country or community. I don’t have a simple solution to these challenges, but I know that we have to have the conversation. I also know that many young men would benefit immensely from an hour at the campfire with our veterans. Better still, I know that many would benefit from learning to fire a rifle at a military range rather than firing one playing Call of Duty alone in their basement.

Service. Sacrifice. Loyalty. Honour. These are just words unless you see these values on display by people you look up to in your life. They are also the building blocks of good character, the likes of which defended our liberties along the cliff walls of Monte La Difensa 80 years ago or on the dusty plains of Kandahar province a decade ago. This Remembrance Week let’s make sure we honour the Canadians who served and sacrificed for a higher purpose throughout our history, and let’s rededicate ourselves to valuing service to country and to one another today.

Mr O'Toole, I hope that we will see more of you, and people like you, in our public service in the days and years to come--thank you.

Thank you for this inspirational piece - and the physical effort that precipitated it.