Help us Obi-Wan Poloz, you're our only hope

Why the Canadian pension model was built to keep politics out of pensions

One of the most troubling aspects of the economic policies of the Trudeau government has been their willingness to allow political ideology to trump sound policy. Over eight years, this has had an incredibly corrosive impact on Canadian prosperity. We saw this last week with the budget narrative surrounding ‘generational fairness’ and increases to capital gains taxes. It was similarly present years ago in the move to tax passive income for small businesses. It was also front and centre in the NAFTA negotiations when the Canadian ‘progressive agenda’ was held out to contrast with President Trump at the expense of our workers.

The government often frames this as their support for ‘the middle class and those working hard to join it’ by standing up against those who are holding you back or ‘not paying their fair share.’ Truth matters less than motivating your base these days. While there is always an element of us versus them with all political parties, the Trudeau government has made it an art form and our economic competitiveness has suffered.

The latest example is the debate surrounding pressuring Canadian pension funds into making more investments in areas of the economy that the government may direct them to. While this issue has suddenly hit mainstream political discourse in Canada, the Trudeau government actually began this approach many years ago. The issue was included in the budget because there has been a steady drumbeat of advocacy over the last year by many respected voices in the Canadian economy. They have been encouraging the government to use the capital found in Canadian pensions to fund everything from the mining sector to technology. Some have even suggested that public pension funds should be used to fund gaps in the healthcare system or other areas of domestic policy. The chorus of voices appeared to reach a crescendo last month when more than 90 senior business leaders signed a letter telling the government that they had "the right, responsibility, and obligation" to make changes to pension management in order to help the economy.

Once this conversation was started, I was not surprised to see it grow because of the attractiveness of the prospect of accessing large pools of capital, but the discussion appears to have forgotten the fact that pension managers have a fiduciary duty to pensioners. Decades ago, Canadian pension funds were given the authority and autonomy to generate the returns needed to meet the demands of pensioners of today and 100 years into the future. Their duty is not to a government, a political ideology, or a sector of the Canadian economy, no matter how important that sector may be to Canada. This perspective is needed in this debate, which is why I am writing this essay.

Fortunately, there is a New Hope for pensioners. In a special message contained in the 2024 Budget tabled in Parliament last week, Minister Freeland called out for help. She announced that former Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz will lead a working group on the pension issue to “explore how to catalyze greater domestic investment opportunities for Canadian pension funds”. Having had a front-row seat to the government’s efforts to ‘catalyze’ such investment in the past, it is my sincere hope that Mr. Poloz cauterizes this debate. His working group should strive to educate Canadians on the value of the Canadian pension model and focus our collective efforts as a country on making Canada a more attractive place to invest. Help us, Obi-Wan Poloz, you’re our only hope.

The Canadian Maple Model has strong roots

At risk of sounding too partisan on this topic, let me say upfront that the Liberal Party deserves a lot of credit for helping make Canada the world leader in public sector pension management. They helped bring effective pension management to the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) in 1997 when there were fears about the viability of the CPP over the long term. These fears were rooted in massive pension liabilities facing the CPP as a result of insufficient contributions and low returns not meeting the challenge of dramatic increases in the life expectancy of Canadian pensioners. People were living far longer than actuarial projections from the origins of the CPP in the 1960s and political parties had been reticent to raise contributions on Canadians and their employers.

The changes made by the Chretien government increased contribution rates to address the shortfall, modernized governance practices, and created an independent and professional CPP Investment Board (CPPIB) to help maximize returns for future generations. Finance Minister Paul Martin addressed the dire state of the CPP in a speech to the House of Commons on February 14, 1997:

The problems facing the CPP are fundamental. The chief actuary of the plan has shown that, without changes, the CPP fund will run out of money in less than 20 years. Without changes, contribution rates would have to increase from under 6 per cent today to over 14 per cent to cover escalating costs. In other words, younger generations would have to pay more than twice as much as now-and get no more for it. This is not fair. This is not affordable.

The creation of the CPPIB and shoring up of our federal pension plan was Paul Martin’s 1997 Valentine’s Day gift to Canadians. Paul Martin and his Deputy Minister David Dodge deserve our appreciation for these changes. We can also thank the pension managers at the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan who inspired them and led many of the innovations at the heart of effective pension management in Canada. CPPIB, Teachers and many other Canadian pension funds were at the vanguard of pension management reform a generation ago to the point that their policies and investment strategies became known as the ‘Canadian’ or ‘Maple Model.’

What made the Maple Model so unique was the fact that Canadian pension funds built strong internal teams to develop and manage investment strategies for long-term growth. In the 1980s and 90s, Canadian pension leaders saw the changing demographics of the country and understood how difficult it could be to meet future liabilities at their present state of returns. They began to restructure their management teams and retool their investment philosophies to drive stronger returns to meet the challenges. They attracted talent by paying market rates and empowered their teams to adopt innovative investment strategies that were quite different from their global peers. Canadian pension funds developed private equity expertise and made direct investments in public and private companies and in diverse asset classes emulating the successful alternative asset investment strategies of another world-class Canadian player, Brookfield. With their large pools of capital and long-term investment horizon, Canadian pension funds became some of the leading investors in infrastructure around the world and became go-to partners for other investment funds.

Most importantly for purposes of the present debate, the Maple Model was founded upon the core principle of independence. Pension funds were shielded from political direction and given the freedom to craft the most effective investment strategies possible. The political independence of the CPPIB was so central to the 1997 reforms that the Chretien government and the 8 provinces that joined them made that they agreed to make it very difficult for future governments to change the system. Any changes to the CPPIB would require two-thirds approval of the provinces representing at least two-thirds of the Canadian population.

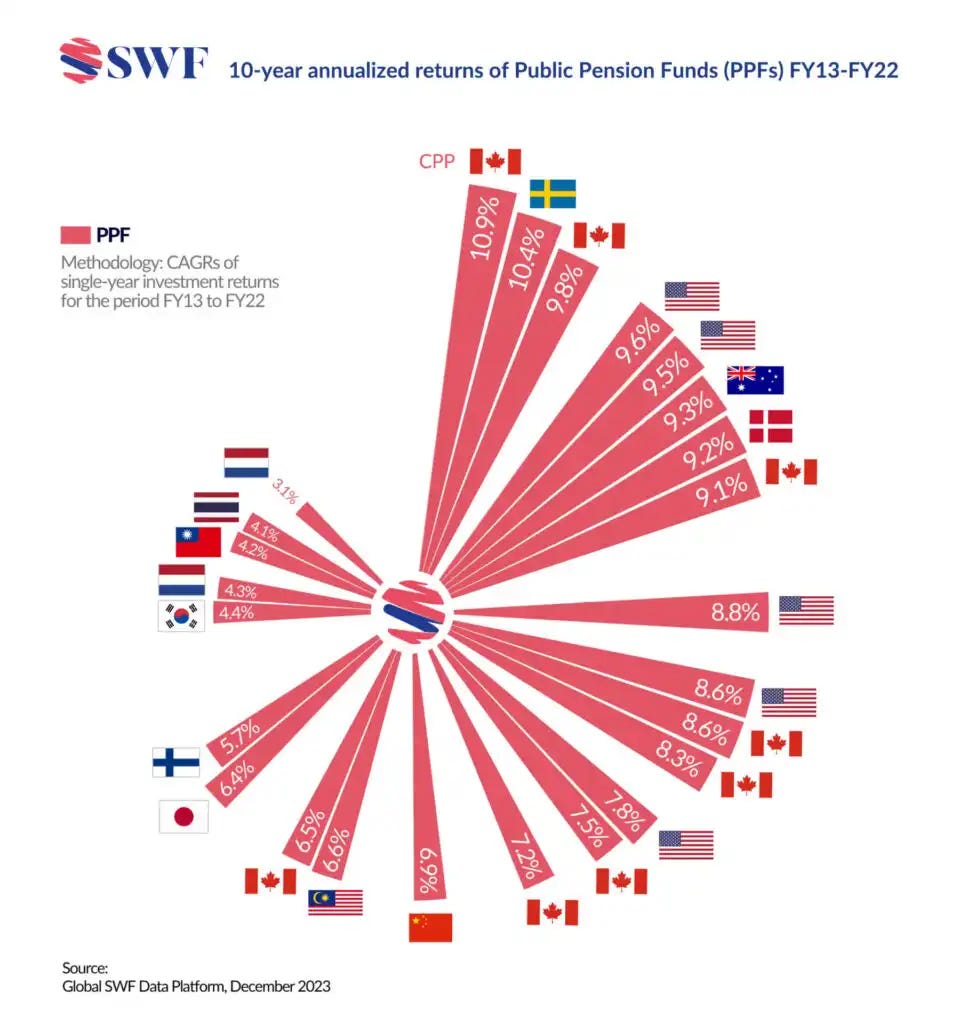

Maple Gold

The result of these changes from a quarter of a century ago speaks for itself. The CPPIB and the other large Canadian public pension funds lead the world in terms of consistently strong returns. The CPP funding shortfall of the 1990s has been transformed into a large surplus that guarantees the pension payments for Canadians for the rest of this century. Over the last two decades, the top eight pension funds in Canada—known as the Maple 8—have consistently ranked in the top echelon of global pension funds in terms of their returns. They also rank high in terms of governance and transparency. If you look at the graphic above, ask yourself if you have ever seen Canadian entries dominate any global economic ranking quite like this. This tremendous success also makes it more astonishing that we are even having a debate about changing a model that is working so well. In fact, the business leaders who developed and led the success of the Maple Model have quietly advised against making any changes.

Pensions, Politics and the United Nations

Political parties look for ways to distinguish themselves from one another and politicians will often put their ideological spin onto all issues. Pensions are not immune from this. We saw this from the start of the CPP reforms in the 1990s when the Reform Party opposed the creation of the CPPIB. For decades the NDP has tried to force the CPP away from investments in sectors ranging from tobacco to energy. I watched some of my Conservative colleagues discuss the need to control where the CPPIB could invest based on geopolitical issues. Even though I was known to be a hawk on issues related to China, I cautioned MPs not to turn a valid criticism of a CPPIB investment into a wider call to halt all investments or for parliament to begin to try and geo-fence investments made by our public pensions.

My concerns about the politicization of pensions are rooted in the Trudeau government’s early attempts to pressure Canadian pension funds into making investments that would complement their campaign for a United Nations (UN) Security Council seat. For several years, the government encouraged public pension funds to increase their investments in the developing world and to place a much higher emphasis on investments that aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In his 2018 appearance at the UN General Assembly, Prime Minister Trudeau announced a $20 million investment to create a Global Investment (GI) Hub in Toronto that was focused on developing “new ways to share Canadian expertise, connect large investors to opportunities at home and abroad, and help the GI Hub continue to develop the resilient, sustainable infrastructure that communities need worldwide.” The “large investors” that the government wanted to connect to UN international development projects were the Canadian public pension plans. This was an attempt to interfere with the independence of the funds.

I became aware of this strategy as the Foreign Affairs Shadow Minister, so I raised my concerns directly with the government. I also did my best to call out what I believed were inappropriate risks the government was taking with the strategy in the limited news coverage of the announcement. I was quite emphatic in my comments after the Prime Minister’s announcement:

“We’re talking people’s retirement. Keep Justin Trudeau’s politics out of it. Keep the UN out of it. [Our] world-class investment managers will decide if a solar investment somewhere or an investment in a developing or emerging economy is appropriate. They should not feel even the gentle nudge of government.”

Even some of the Liberal members of the Foreign Affairs Committee shared my concerns and were worried that this policy would push public pension funds to invest in some of the higher-risk jurisdictions in the world. The committee also knew that most countries considered the UN SDGs to be aspirational ‘goals’ and not something that other countries were forcing on either their public or private sectors.

Fortunately for Canadian pensioners, not much came from this GI Hub announcement. Two years later, Canada lost its bid for the Security Council seat and I am not aware of any Maple 8 funds making an investment because of this pressure. What the entire exercise proved to me was that politicians could very easily view the large pools of capital in the pension plans through their political lens and that could put future returns at risk. Whether their political agenda was in the public interest or not, changing the approach to the Maple Model was a slippery slope that the CPPIB was set up to prevent.

If you can’t change the world, change yourself

In 1999, around the same time the CPPIB was first receiving funds to invest for Canadians, politicians were already pressuring the government to interfere in this new organization’s investment decisions. In this case, it was the NDP and the ethical implications of the CPP holding public equities related to tobacco. The response from Paul Martin back then should be the answer to the debate we are having today: “[I]t is very important that there not be political interference in the administration of the funds by the government.”

Today, the world is even more uncertain and Paul Martin’s advice is even more important. Globalization is unwinding, war and conflict are on the rise, populism is driving isolationism and AI has the potential to dramatically change our labour markets and social contract. The post-World War II era of stability is over and the massive baby boomer generation is largely retired. All this means that we are living in uncertain times and may be entering a period of persistent inflation and low investment returns. The geopolitical and investment risks the world is facing are unprecedented, which is why it is even more important to let the professional management teams of the Canadian public pensions do their job. The surpluses that many of the Maple 8 have built up may be needed to help their funds weather future economic storms.

I have confidence in the wise Jedi chosen for this assignment. Obi-Wan Poloz knows that the uncertainty of this era means Canadians will need the stability and security of an effective pension plan more than ever before. I hope that his working group will recommend that Canada gets its own act in gear and leave the Maple Model alone. If we want to see more capital investment in Canada, the answer is to make Canada a more welcome place for investment. For a country with a frontier heritage, a history of innovation, and capital markets that are known for exploration, resources, and engineering, it is astounding that we have allowed ourselves to develop a reputation as a country where capital goes to die. We can and must fix this.

There are many things his working group should recommend. Canada needs single and swift reviews of large projects. We need to incentivize risk-taking and encourage people to generate income from the commercialization of their intellectual property in Canada. We need a single, national securities regulator. We need to review the excessive application of the precautionary principle by governments. We need to get the energy transition right and realize that energy—particularly Canadian LNG—helps us pay for our decarbonization and electrification efforts. We need to do a lot of things to make our country attractive to more investment, but messing with the Maple Model is not one of them.

Post Script

One caution I would make is that as strong as the Maple 8 are, they must be more prudent about the pace and intensity surrounding many of their sustainability and Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives. I say this as someone who has taken a very public stand on a responsible energy transition and fought back hard against the polarization surrounding ESG and other corporate social responsibility initiatives. Pension executives must reflect on these issues from both a financial and public confidence point of view.

Public relations pressures and rising shareholder activism have indirectly permitted some political ideology to creep into investment decision-making. Initiatives are being signed onto in lockstep by the industry even when they seem difficult to achieve. Returns of Canadian public pension funds remain impressive, but I worry that they could have been stronger if the energy transition was more balanced. I also worry that this absence of balance may erode public confidence at a time of rising polarization. With some initiatives, altruism appears to be eclipsing realism and this can amount to political interference by stealth.

I add this postscript with respect because I want our pension funds to be responsible and sustainable, but I never want them to lose sight of the critical importance of independence to the success of the Maple Model.

This is an excellent argument for government sticking to what it does best. It may be insanely hard for large governments to harness, say, technology in the service of productivity (https://www.theaudit.ca/p/government-productivity-after-four), but it's not all hopeless.

Ah, Erin. You've been away too long already. Navs rule.