Canada's Most Courageous Pilot of WWII is our Least Known Hero

The Triumph and Tragedy of Byron Rawson

The centennial year for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) is coming to a close. Throughout 2024 there have been a series of important commemoration events marking the century of service that the RCAF has provided to Canada and the world. From the Silver Dart on the icy lakes of Cape Breton, to the powerful CF-35s that will soon arrive in Cold Lake and Bagotville, Canadian aviators have always distinguished themselves as they pushed the limits of air power. They also helped explore, map and defend Canada and the United States. The true power of the RCAF, however, has never been the roar of the mighty engines of its aircraft. The strength of the RCAF has always been found in the incredibly brave men and women who have stepped up to serve.

As the year comes to an end, I wanted my last essay of 2024 to focus on the RCAF and the incredibly brave exploits of just one pilot. On pilot out of thousands of Canadians who have served in the RCAF over the last hundred years. One name that most Canadians have never heard of because his story represents both the triumph and tragedy of war. His story has also been on my mind throughout Christmas this year for reasons that will soon become clear.

Wing Commander Byron Rawson, DFC

Byron Rawson was born in Northern Ontario in 1922. His family lived in a little town with a lovely name; Smooth Rock Falls. Byron was raised with a profound sense of civic duty, patriotism and deep religious faith. His father, Norman Rawson, had served in the Great War rising up from the rank of Private to Captain. After the war, Norman Rawson became a Methodist Minister and would often use both his Reverend and Captain rank as salutations. This was a demonstration of the Rawson family commitment of service to God and country.

Over the course of several church assignments Rev. Rawson built up a level of recognition because of his impressive oratory and his civic mindedness. This led to several moves to more prominent pulpits in larger communities. Byron’s mother Mazie raised the four children as the family moved from Northern Ontario to Ottawa and eventually Hamilton, where Rev. Rawson led the large Centenary Church congregation. The Reverend was also a trusted advisor to business leaders and politicians in Hamilton and across Ontario. A patriarch that Byron looked up to.

Byron was the only boy in the family, and by the age of 17 he had graduated high school and enrolled in McMaster University with a plan to become a lawyer. In his first year of university in 1940, Byron (now known as Barney to most of his friends) watched as Nazi Germany advanced across Europe bringing Canada into the war. His father began speaking in church and around the community on the importance of national service, so naturally Barney joined the Canadian Officers' Training Corps unit at McMaster while completing his first year. At the end of the school year, he enlisted in the RCAF. By the time he turned 19, Rawson was a fully qualified pilot and would soon be flying Wellington and Halifax bombers with the newly formed No. 429 (Bison) RCAF Squadron as part of Bomber Command.

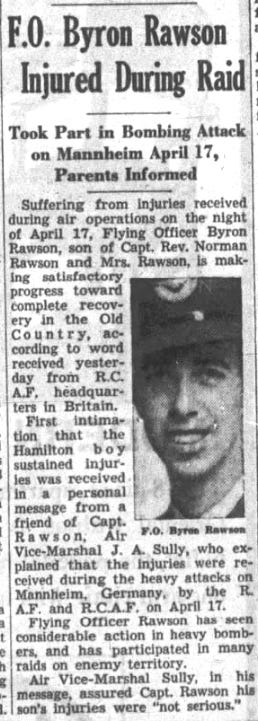

It was at 429 Squadron that Barney Rawson’s courage and remarkable flying abilities began to be recognized. Over his first few months he took part in multiple bombing runs on the industrial cities of Dortmund, Dusseldorf, Berlin, Frankfurt, Stuttgart as well as on the German U-boat pens in Brest, France. Rawson gained attention for his bravery, cool head and his remarkable precision as a pilot. With Bomber Command taking heavy losses on each mission, Rawson’s crew always seemed to make it back to base. In one mission - a bombing run over Mannheim in April 1943 - his aircraft was badly damaged and Rawson himself was injured by flak, but he still managed to get the crew home safely. He was hospitalized, but quickly recovered and resumed his flying duties. Exploits such as this continued to build his reputation with the senior ranks of the RCAF and the Royal Air Force (RAF) and led to rapid promotions.

By October 3, 1943, Barney Rawson had been promoted to Flight Lieutenant and flew his twenty-seventh mission as part in a massive 547-plane bombing run over the industrial city of Kassel. The next day, Buckingham Palace announced that Rawson would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in recognition of his steadfast courage and flying abilities. One senior Bomber Command officer said this about the recognition for Rawson:

“in terms of danger and death…[Rawson made] a far greater … contribution than that of any other fighting man, RAF, Navy or Army.”

The formal DFC citation was a little more dispassionate not mentioning death, but stated simply that Rawson was “a fine example of courage, enthusiasm and devotion to duty”. At the age of 20, Rawson was shooting up the ranks and was already being recognized as one of the bravest and most capable bombing pilots in the war.

The Toll of Bomber Command

A month after receiving his DFC in the presence of the King and a young Princess Elizabeth, Barney Rawson completed his thirty missions as a Bomber Command pilot. This was a threshold that less than half of the aircrews of Bomber Command would ever reach. In accordance with both Royal Air Force (RAF) and RCAF policy, crews who completed their 30 missions (or 200 hours total flight time) were to be assigned to a ground tour for at least six-months. This policy was intended to avoid burnout and allow crews to recover from the incredible toll of the bombing mission.

To understand why aircrew were burning out in Bomber Command, it is important to appreciate the incredible danger of these missions and the trauma aircrew experienced. Aircrew saw their comrades perish around them in the skies and were powerless to help them. Each crew was never sure if they were going to return from a mission or not. This created a gallows-like atmosphere on Bomber Command bases and high instances of physical and mental stress and illness. Historian Patrick Bishop described this sense of dread in his book Bomber Boys. Fighting Back, 1940-19451:

The swing of the scythe was impressively arbitrary. One crew member might be hit and leak blood all over their Lancaster while the others were unscathed. A pilot might have an eye and nose shot away; in this case he flew on, valiantly trying to fly the plane and his crew back to safety. Back at base, those who failed to return were quickly wiped from the slate. Every man kept his wash bag in a satchel on a peg above his bed so that in case he died, all evidence of his existence could quickly be removed and the next man moved in…The spirit of death was everywhere.

Far too many crews has their names wiped from the slate and their wash bag removed from their bunk as the war progressed. By the end of the war, for every 100 aircrew who flew as part of Bomber Command, 45 were killed, 6 were seriously wounded, 8 became prisoners of war, and just 41 survived the war2. The casualty rate was greater than 50% making Bomber Command the Allied branch of service with the highest rate of death or injury in the war. In fact, Bomber Command accounted for 1/10th of all allied casualties and almost a quarter of Canada’s war dead.

Aircrews were also well aware of the death and destruction their bombing missions brought on the ground. While the mission of Bomber Command was to destroy the industrial war machine of Germany, there were often hundreds of faceless civilian casualties with each mission. Aircrew knew that the accuracy of the bomb drops was a constant challenge, so they mental trauma crews faced accumulated with each mission. By the end of the war, bombing missions had also shifted from breaking the back of industry to breaking the morale of the Germans. This made the mental stress of bombing missions more difficult for aircrews to process.

By the end of 1943, Rawson was once again promoted and was now a Squadron Leader assigned to be the Group Tactics Officer for 6 (RCAF) Group as part of his post-30 missions ground assignment. Despite his rapid promotion and the ability for him to stay safe on the ground, Rawson began to lobby to keep flying. In particular, he wanted to join the elite Pathfinder Force of Bomber Command. The Pathfinder Force (PFF) had been created in August 1942 to help improve the terrible accuracy rate of the bombing missions. The rationale was to assemble an experienced group of aircrew and provide them with the latest navigational aides and other technical equipment so that they could properly identify the targets and drop flares to allow the main bombing force behind them to find their mark.

Prior to being assigned to the PFF and prior to the completion of his full six-month break from flying, Rawson began to fly missions as a second pilot for other crews. This included flying on a D-Day Plus 1 mission to bomb the Paris rail yards to help limit German troop movements in response to the Normandy landings. Barney Rawson wanted to be in the action at all times.

Following his D-Day plus exploits, Rawson was finally granted his request to join the Pathfinders and became the operational commander of the PFF Wing of 8 Group. At the age of 21, Byron Rawson was again promoted and became the youngest Wing Commander in the Commonwealth. Despite his senior rank he was volunteering to face the greatest risks of the war with the PFF. He flew in this operational command role for the remainder of the war. His final mission was on April 10, 1945 targeting German ships and submarines in the port of Kiel just a few weeks before the surrender of Nazi Germany.

At the end of his second operational tour with Bomber Command, Wing Commander Byron Rawson had flown 53 missions with the last twenty or so with the Pathfinder Force. He was awarded a second DFC after the Kiel mission, which added a bar to his DFC from 1943. His accomplishments were remarkable. Over 250,000 Canadians served in the RCAF during the war and a total of 4,018 DFCs were awarded to RCAF aircrew. Byron Rawson was one of only 213 Canadians to be awarded a second DFC and one of an even smaller group from Bomber Command. He ended the war as the youngest senior air force officer in the Commonwealth and one of the bravest and most accomplished RCAF pilots of the war.

Invisible Wounds of War

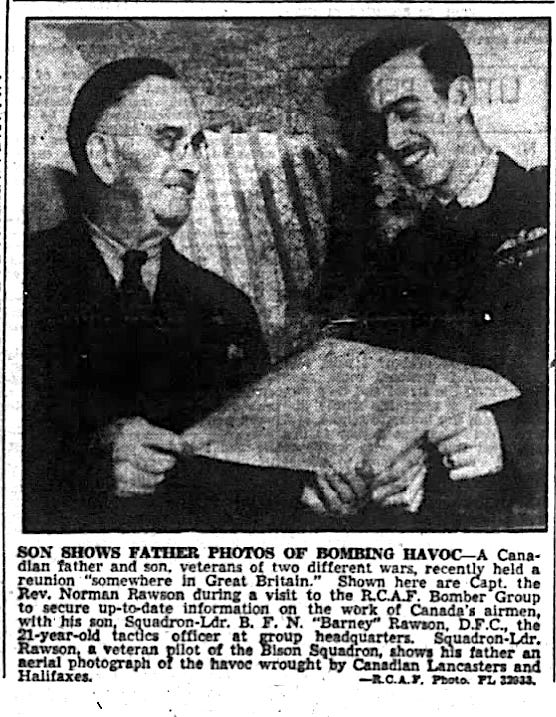

Byron Rawson was a man of deep conviction and religious faith. This is what drove him to enlist and continued to drive him to taking on more dangerous missions as a pilot. By the midpoint of the war, his father Rev. Norman Rawson had become a well known religious figure in Canada. His patriotic speeches and his own personal history of service led United Church congregations to request him as a speaker and he travelled the country speaking about the civic duty of supporting the war effort. The Canadian government even sent Rev. Rawson to Europe to boost the morale of the troops and return to Canada with stories from the European theatre. During this trip he was able to visit with Byron and this father-son reunion was promoted back home in Canada. Young Barney believed that he had the expectations of his family and the nation on his shoulders as he took to the skies on his dangerous missions.

Rawson and his Bomber Command colleagues had to face more than just the psychological fear of death that came with each mission. The strategic bombing focus of Bomber Command meant that these young men also had to navigate the complex moral terrain of their missions. The bombing campaign was an important part of the ultimate Allied victory, but each raid resulted in hundreds or thousands of civilian casualties. The crews constantly struggled with this reality.

Over the course of the war, the Allies dropped over 2 million tonnes of bombs in the European theatre with more than half being focused on Germany. Estimates of the civilian deaths from the bombing campaign have ranged from 380,000 to 600,0003. These deaths seemed almost invisible to aircrews dropping bombs from thousands of feet in the air, but Rawson and his comrades knew their missions often killed innocent civilians. The crews would have a sense of survivor’s guilt for coming home when far too many of their friends did not, but they were also vulnerable to a form of moral injury from the deaths on the ground. Dr. Heather Venable, a professor at the United States Air Force’s Air Command and Staff College, has written about this acute mental anguish on WWII bomber crews:

The crews over Germany may have been thousands of feet from their victims, but those victims were often civilians who did not present appealing targets…Regardless of the altitude, living with killing after surviving being killed posed psychological and moral challenges for those lucky enough to survive the trauma of war.4

Byron Rawson knew the pressures and psychological toll better than most and struggled with it. His family knew the toll that civilian deaths would have taken on him due to his deep faith and character. This is likely the reason why Rawson was so driven to be transferred to the Pathfinder Force. He wanted to help make the bombing missions more accurate to reduce civilian casualties and reduce the moral burden on his crews. He was a Wing Commander who led by example and was willing to take on greater personal risk to reduce the risk of civilian casualties on the ground and the mental burden on his comrades in the air.

Forgetting Bomber Command

When the war ended in Europe, Bomber Command aircrew soon noticed that politicians and military leaders attempted to minimize their contribution and slowly disavow the use of precision bombing during the war. While the ability to strike German targets during the Battle of Britain and the dark days of the Blitz was a rallying point for the British people at their darkest hours in 1940 and 1941, the incendiary bombing of Dresden and other cities in the final months of the war in 1945 clouded the important role played by Bomber Command.

Following Victory in Europe, the role of Bomber Command was strategically downplayed by the United Kingdom and its allies. Prime Minister Winston Churchill made no mention of the contribution of Bomber Command in his May 8, 1945 victory speech that touched on all other elements of the war effort. There was no campaign medal issued to Bomber Command, and its high-profile commander, Air Marshall Arthur “Bomber” Harris, was controversially denied a peerage by the government5. After making a significant contribution to the allied victory and taking the greatest personal risks of the war, many Bomber Command veterans began to feel abandoned by their governments. The fighter pilots of the Battle of Britain were the famous ‘few’ to which so much was owed6, but the pilots and crew of Bomber Command soon became the forgotten.

When Byron Rawson returned home at the young age of 22, he was a very different man compared to the boyish 18 year old who had left for war. The visible accolades of his senior rank and his prestigious DFC with bar could not hide or heal the invisible scars of his wartime service. He was released from the military in September 1945 and began to pick up his life from where he had left it. He enrolled in Osgoode Hall to accelerate his path to becoming a lawyer and found a lawyer in Hamilton to article with. He began to reconnect with friends and family. By all outward appearances, he seemed to be adjusting well, but friends and family were noticing a change in him. He was having difficulty sleeping. He seemed “morose and cheerless” to some of his friends. His roommate in Toronto remarked that a despondent Rawson had told him that ‘death in a doomed aircraft’ was the preferred manner to die7. While the exploits of Bomber Command were being forgotten by politicians and the public, the veterans themselves were unable to forget the trauma of their service. They were now isolated from the comrades that understood their struggles and found it difficult to find meaning in picking up their old lives from before the war.

On December 3, 1945, Rawson celebrated his 23rd birthday in Toronto struggling with the mental injuries from the war. A few weeks later, he travelled to Hamilton for Christmas. He died by suicide in his parent’s home on December 23rd just three months after leaving the RCAF. “Dies suddenly” was how the Hamilton Spectator announced his death at the time to a stunned community. To compound this horror on his family, his death was not determined to be related to his service because the war was over and he was a civilian. Byron Rawson’s death went largely unacknowledged by his community and the country he had served so faithfully. One of the bravest and most accomplished RCAF pilots of the Second World War was soon forgotten by almost everyone but his family for over half a century.

A Positive Post-Script

Over the last two decades, Canada has matured in the way we look at mental health. The country has also been re-examining how we speak responsibly about suicide and how we tackle previously unspoken parts of our military history. Today, we understand the invisible wounds of service in the form of operational stress injuries like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and moral injury. The Canadian Armed Forces now strives to prepare soldiers, sailors and airmen and women for encountering trauma in their service for the country. This begins with resiliency training before a mission and decompression procedures afterward. While there is still a long way to go to continue to reduce stigma and improve the speed of access to treatment, we are now able to talk about, treat and help people heal from mental health injuries. This is positive and must continue.

Byron Rawson was a casualty the country did not recognize in 1945, but his story has been rediscovered and his memory restored thanks to the advocacy of volunteers like Toronto lawyer and veteran Patrick Shea. Shea assembled the military and medical documentation required to request that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) to reconsider the death of Byron Rawson. In 2018, the CWGC determined that his death was attributable to his military service in Bomber Command. To the best knowledge of all involved in this process, this was the first such case in the Commonwealth where a post-release death was reclassified as service related decades after the fact.

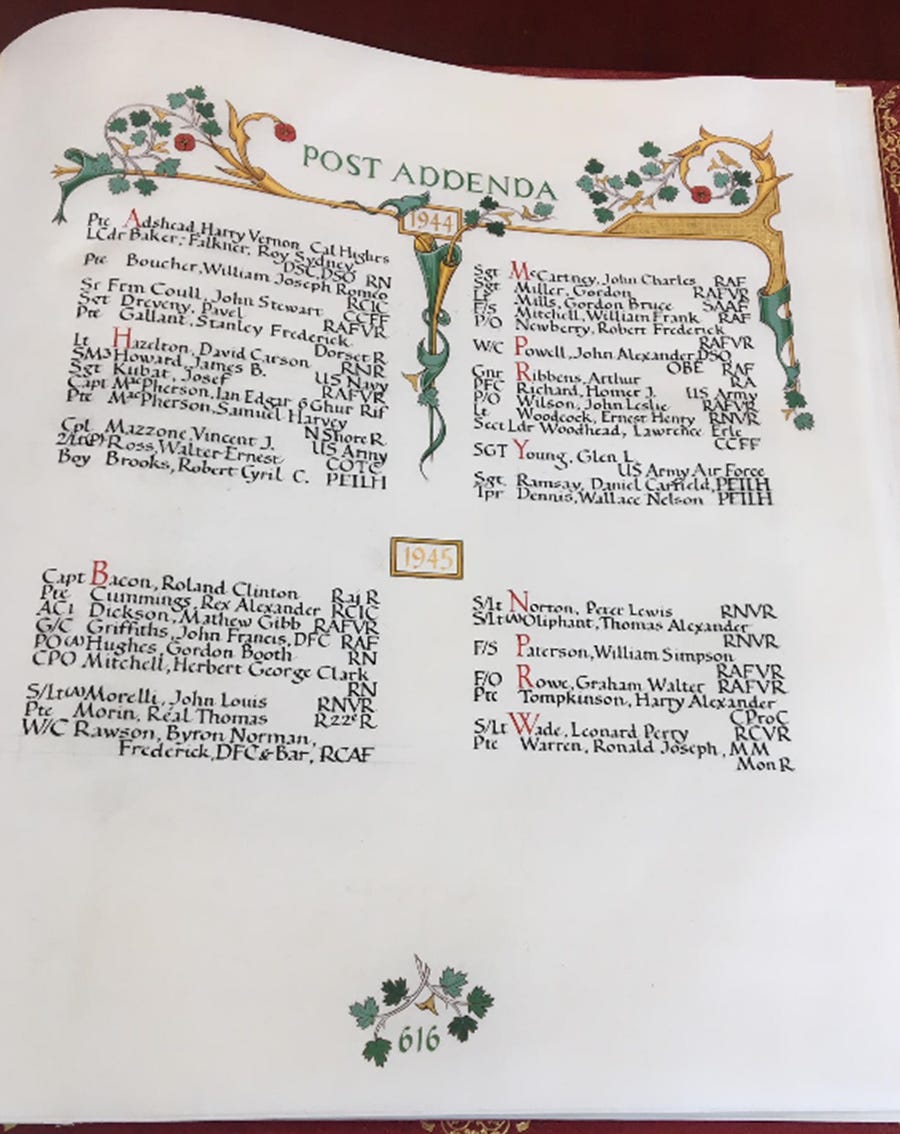

A new gravestone was added to Rawson’s understated plot at Woodland Cemetery in Hamilton. It bears his rank, decorations and the inscription “A Brave Warrior, A Son of Christ” to denote his deep faith and courageous service. The CWGC calligrapher also added Rawson’s name to the Book of Remembrance in Ottawa, which will be housed in the Memorial Chamber for time eternal. The very fact that the Canadian Books of Remembrance contain a ‘Post Addenda’ section confirms that it is never too late for a grateful nation to honour its fallen.

In the last two decades, Bomber Command Veterans have also been finally receiving the recognition they missed in the years after the war. In 1985, a group of amateur historians and civic volunteers in Nanton, Alberta formed a group to restore Lancaster bomber monument that had been on display in the town since the 1960s. This initiative ended up attracting such interest that the Bomber Command Museum of Canada was born and it remains the flagship Canadian tribute to our role in this important part of the war.

In 2012, an official RAF and Commonwealth Bomber Command Memorial was opened in central London to honour the sacrifice of Allied aircrew and to commemorate the loss of civilian life as well. Queen Elizabeth II opened the memorial as part of her Diamond Jubilee celebrations showing that society had finally come to terms with honouring Bomber Command veterans. In conjunction with this opening, the Harper government announced the creation of a military honour to recognize Bomber Command veterans in Canada. A special Bomber Command bar was created for veterans to wear on their Canadian Volunteer Service Medal. It was estimated that at least 1,500 Bomber Command veterans were still living to receive the honour personally at the time, but the initiative also allowed families to add this special bar to their loved ones medal set posthumously.

The celebration of the RCAF Centenary is coming to an end, but our recognition and appreciation of the incredible Canadians who serve must continue. Byron Rawson’s story also reminds us of our duty to remember both the victories and the tragedies of war and service to country.

Addendum: this essay was greatly assisted by the research conducted by Patrick Shea and is based on a speech I gave to the RCAF Centennial Conference hosted by the University of Calgary Centre for Military, Security and Strategic Studies in November 2024. A shorter version of the Rawson story also appeared as an op-ed I submitted to the Toronto Sun for Remembrance Day.

Patrick Bishop, Bomber Boys. Fighting Back, 1940-1945 (London: HarperPress, 2007).

Statistics taken from https://www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca/commandlosses.html

https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/horror-and-glory-bomber-command-british-memories-1945.html

Heather Venable, Living with Killing: World War II US Bomber Crews, Æther: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower, Vol. 2, No. 3, Special Focus: Moral Injury (Fall 2023)

Some sources state he declined a peerage because of the lack of a Bomber Command medal and treatment of the force after the war.

“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” A line from Churchill’s speech to the House of Commons on August 20, 1940 thanking the Battle of Britain pilots known as the ‘few’. More on this important speech here: https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1940-the-finest-hour/the-few/

https://www.mcmaster.ca/ua/alumni/ww2honourroll/rawson.html

Great work Erin. It is an important story and you tell it well. Well done.

Excellent work. You shine a light on a disgraceful aspect of our post-war history and, rightly, on the efforts made in the 21st Century to right the wrongs visited upon our brave ‘bomber boys’. Keep up the good work.